The rhythm of life in Dar es Salaam has shifted from a steady flow of water to a desperate midnight watch. Across the city’s neighborhoods, dry taps have become a common frustration, forcing residents to choose between using their meager supply for cooking or for bathing.

Residents say since late November 2025, households have seen their taps run dry, leaving families to rely on rare moments—often in the dead of night—when water might briefly flow.

“Since the end of November, that is when the water cut off,” explained Dorothy Ndalu, a resident of Mbezi, during an interview with Nijuze. She noted the psychological toll, adding, “Even if you are in your room and you hear the water ‘chu chu chu chu,’ you wake up just to set the buckets.”

This shortage follows a punishing seven-month dry spell between May and October 2025 that crippled the city’s primary water sources. President Samia Hassan addressed the nation on New Year’s Eve, noting that the depletion of the Ruvu Juu and Ruvu Chini sources created a significant challenge.

“We were hit by a shortage of rain… which brought drought and a decrease in water sources,” the President stated. She emphasized emergency measures, saying, “The government ensured that all nearby water sources directed water to the city, as well as reviving wells that were not working.”

However, the weight of this environmental shift is not shared equally. In a city where women are the primary managers of the home, the lack of water has transformed domestic duties into an exhausting physical and economic struggle.

The physical and economic toll of a dry tap

For those managing households, the water crisis is a thief of time and energy. Esther Genes, a resident of Mtongani, explained in an interview with our reporter that the burden falls squarely on women while men are away at work.

“Those of us who stay at home get physically tired because the places where you can get water are far from here,” she said. “It forces you to walk far from your homes searching for water and then return.”

This exhaustion is coupled with a staggering financial cost. In Mbezi, residents report that the price for a 1,000-liter tank from private vendors has soared to TZS 70,000.

Ms Ndalu pointed out that while water supply vanished, billing remained constant. “Surprisingly, the bill for November and December is the same,” she noted. “Which until now I haven’t paid.”

Beyond the home, the scarcity is paralyzing women’s livelihoods. Lucia, a resident of Mwenge, observed that hair salons—vital economic lifelines—are being forced to close.

She recalled a stylist telling her, “Currently, if you come to wash hair, come with your own water to the salon.” Lucia explained the broader impact fueled by the scarcity. “You find a person again has to stay at home, she goes backward again economically… In the end, the capital itself runs out.”

A quiet crisis of health and dignity

Without reliable water for sanitation, maintaining personal hygiene becomes a daily gamble. Lucia noted that in crowded living areas where ten people might share a single toilet, the lack of flushing water is said to have led to a spike in infections.

“It brings many effects like… infections of these urinary tract diseases like UTI,” she said. “We stay in these places with many people, one toilet for ten people… and the water itself is not there.”

For women, the crisis is even more acute during menstruation. Ms Genes emphasized that the biological need for cleanliness does not stop when the water does, forcing difficult “balancing” acts.

“A woman must maintain cleanliness more during this period than other ordinary days,” she explained. “Therefore, those things must be removed… and we clean ourselves by using water. So that thing has also cost us very, very, very much.”

Lucia added that hygiene becomes a problem during menses: “You wonder if you should bathe or leave this water as a reserve.”

The lack of water also erodes the sense of dignity that comes with a clean home. Ms Genes explained that women often wait for weeks to wash clothes, leading to a buildup of dirt.

“Lack of water also increases the dirt in the homes because you find you must now wait for the water to be a lot so you can wash clothes,” she added. “A woman is created with a persona of cleanliness. It is not good for a woman to be excessively dirty.”

The global adaptation finance gap

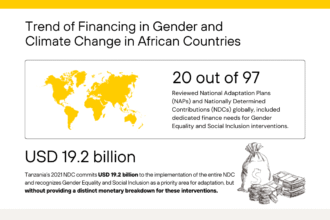

The struggles in Dar es Salaam’s streets are deeply connected to global climate politics. The current Tanzania’s Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) estimates that the country needs over USD 19.2 billion to implement its climate goals, a sum that requires significant international support.

However, the 2025 Adaptation Gap Report warns that “the world is gearing up for climate resilience—without the money to get there.”

At the recent COP30 negotiations, leaders introduced the “Belém gender action plan” to address the “differentiated impacts of climate change” on women and girls.

Tanzania has mirrored these efforts in its own National Climate Change Response Strategy 2021-2026, which prioritizes gender mainstreaming. Yet, as the interviews in Mtongani and Mwenge reveal, there is a disconnect between high-level policy and the reality of a dry tap.

While the government continues to work on long-term infrastructure such as the Kidunda Dam and the Kimbiji-Mpera water project, the immediate future for Dar es Salaam’s women remains in the hands of the developed nations that contribute heavily to the pollution leading to climate change impacts like these in Dar es Salaam and everywhere else in the world.