A new analysis shows that although Tanzania places strong emphasis on gender equality in its climate plans, it has not identified how much money is needed to support these gender-related actions. This gap appears at a time when developing countries face rapidly increasing adaptation costs, far beyond what current international funding can cover.

The official documents for Nationally Determined Contribution released in 2021, shows that Tanzania has not calculated a specific financial requirement for its gender-related (GESI) measures in either its National Adaptation Plans or its NDC. The policies exist, but the actual cost of delivering them is not defined.

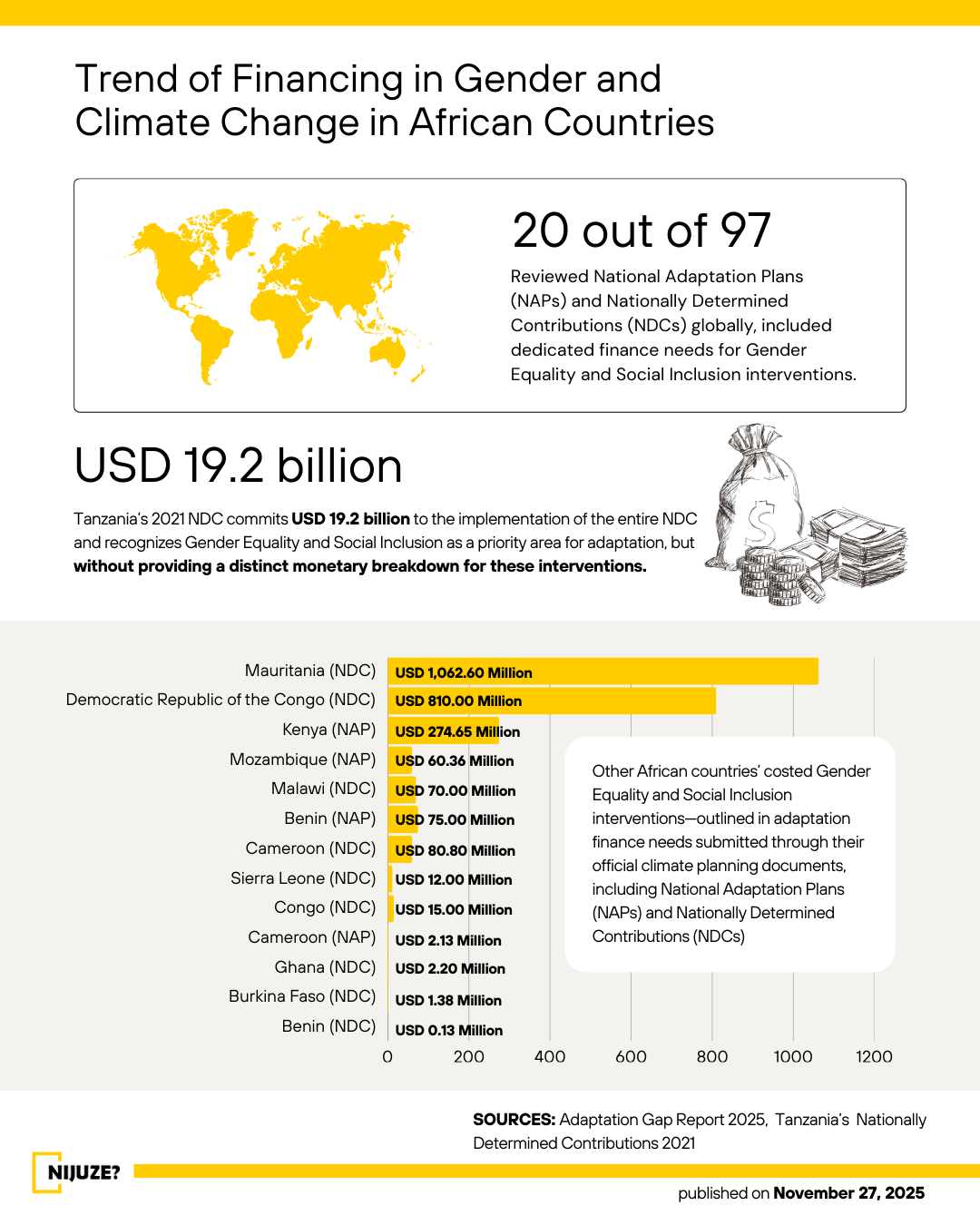

Tanzania has, however, outlined the overall cost of its entire climate plan. Implementing the NDC—from adaptation to mitigation—would require USD 19.23 billion. The country stresses that it can only achieve this with reliable international financial and technological support.

The pressure is growing: responding to current climate risks already costs Tanzania about USD 500 million a year, and this could rise to USD 1 billion annually by 2030.

How other countries cost gender measures

Tanzania is not the only country struggling to assign a price tag to gender priorities. According to the Adaptation Gap Report, only 20 developing countries worldwide have identified specific finance needs for gender and social inclusion in their NDCs or NAPs.

Even among those that have done so, the level of commitment varies widely:

- Mauritania plans for 10% of its adaptation finance to go to Gender Equality and Social Inclusion.

- Burkina Faso and Ghana allocate less than 0.1%.

Across all 20 countries, the average is just 2.32% of total adaptation finance needs.

These numbers show that while many African countries mention gender in their climate plans—using either mainstreaming or dedicated approaches—clear, protected funding often falls far behind the political promises.

Reporting gaps and limited gender transformation

The review also points out that very few countries track the results of their gender work. Globally, only 4% of reported adaptation outcomes are directly related to gender or broader social inclusion.

And while many countries claim to use “gender-sensitive” approaches, the analysis found no examples of truly “gender-transformative” approaches—efforts that change existing power structures and create long-term gender equity.

For Tanzania, the challenge is not recognizing the importance of gender—it already does. The challenge lies in translating those commitments into specific, funded actions. Without dedicated budgets, protecting women and other vulnerable groups from intensifying climate impacts remains far more difficult.