Climate adaptation negotiations at COP30 in Belém have entered a tense phase as developing countries confront wealthy nations over a widening gulf between adaptation needs and the finance on offer. For many communities facing intensifying floods, droughts, and climate-linked losses, the summit is unfolding against a stark new warning: the world is trying to build climate resilience without the money to do it.

The UN Adaptation Gap Report 2025, released as delegates gathered in Brazil, paints a severe picture. Developing countries will require US$310–365 billion every year by 2035 to adapt to escalating climate impacts, yet only US$26 billion is currently flowing from international public adaptation finance. That leaves an annual shortfall of US$284–339 billion, a gap the report says is not reducing, but expanding.

The report adds that adaptation needs are now 12–14 times higher than existing finance flows. Even the most ambitious global targets fall short: the Glasgow Climate Pact’s US$40 billion-per-year adaptation goal for 2025 is on track to be missed, while the proposed US$300 billion NCQG target for both mitigation and adaptation by 2035 does not even cover adaptation needs alone. Accounting for inflation, adaptation costs could reach US$440–520 billion annually by 2035.

Widening adaptation finance gap fuels urgency

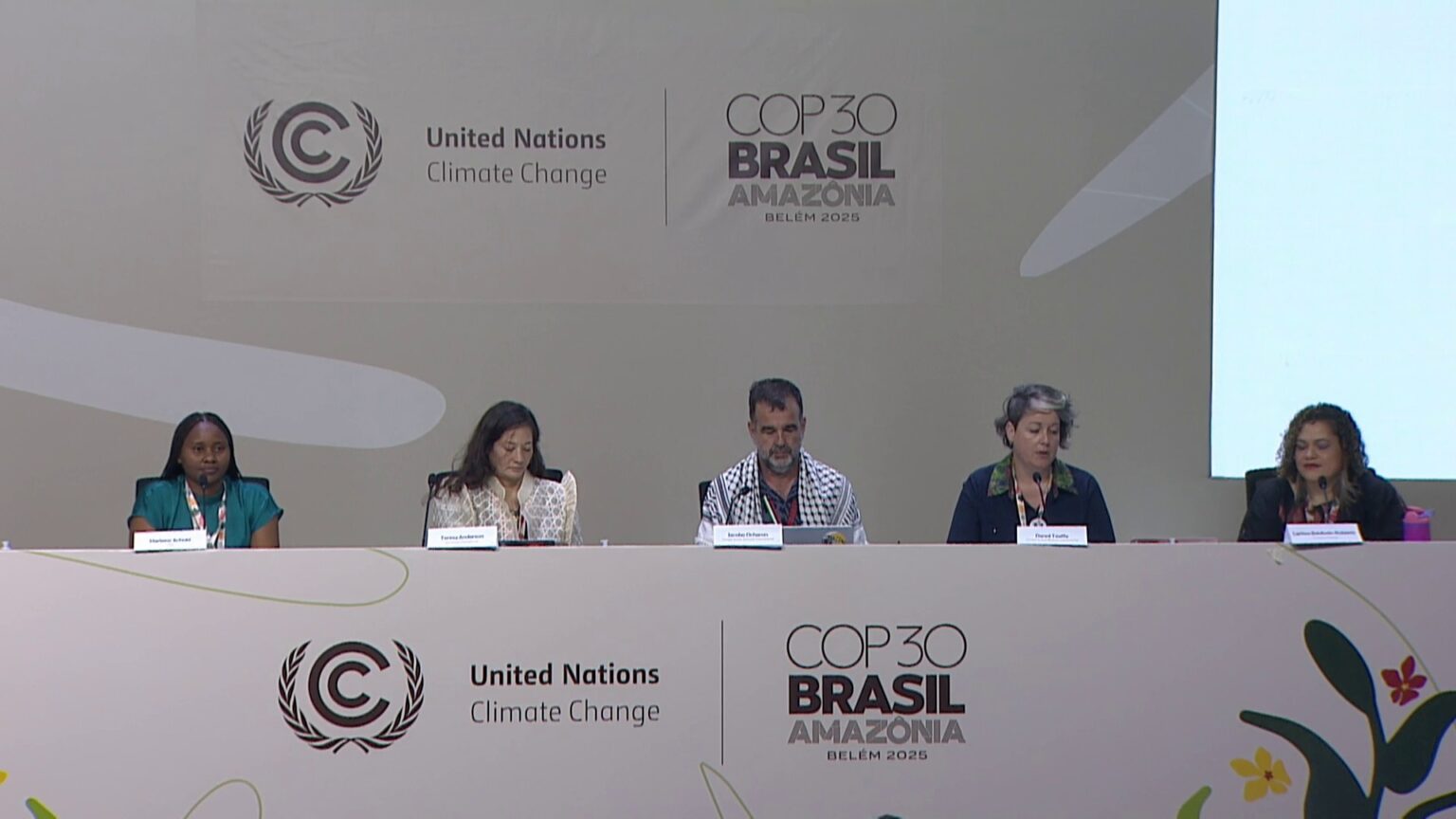

Speaking during a CAN International press conference held on November 14, 2025, at the COP30 venues in Belem, Brazil, Marlene Achoki, Global Policy Co-Lead for Climate Justice at CARE International — said the report confirms what communities on the frontlines have long experienced.

“The adaptation finance gap is widening. Even the NCQG amounts only cannot be sufficient for adaptation action,” she explained in a blunt voice. “We just do not want to have indicators that are just a bluff, but we want finance to help us implement the actions at the ground, but also measure what is flowing in terms of adaptation finance.”

Achoki stressed that adaptation finance must not push developing countries deeper into debt. “It has to be from public sources. It has to be easily accessible,” she said, painting a picture of what’s currently happening in Africa. “We do not want adaptation finance to come from private sources. We do not want countries to take loans to address adaptation crisis.”

She added that many proposed indicators fail to reflect the realities of developing nations. “Some of them are very prescriptive. And developing countries are saying these indicators do not meet the context of the needs that you want to look into. Without the money, we cannot do anything.”

Political tensions over justice and obligations

Inside the official negotiation rooms, finance remains the fault line running through every agenda item.

According to Jacobo Ocharon, Head of Political Strategies at CAN International – the core struggle is about justice and responsibility — and who pays for climate action.

At the same press conference, Ocharon noted: “This climate crisis is, at its core, a crisis of injustice,” he went on stressing that “Those who contributed the least are the ones that are suffering the most. And multilateral processes like this COP should be focused on confronting exactly that.”

Ocharon mentioned that developed nations arrived in Belém “short again on emissions reductions, short on climate finance, and short on ensuring just transition,” leaving Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement — which legally requires developed countries to provide finance — at the center of the deadlock. “Approving indicators without addressing the final needs to meet them is not technical. It’s political. And it goes to the heart of the justice gap we are talking about.”

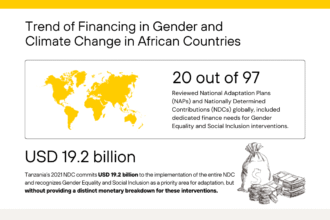

Tanzania seeks grants amid a widening UN-reported finance gap

Back in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania has made its expectations clear. Days before the COP30, Sarah Pima, the Gender and Youth Lead Coordinator for the African Group of Negotiators (AGN), told Nijuze that any financial commitments must come without interest or debt risk.

“We expect the money to increase, but these funds should not increase in the form of loans,” she said on 8 November. “They should increase in the form of grants. We know our country is still developing and it needs finance that will not have interest.”

Pima said Tanzania is prioritising “means of implementation” — including technology, capacity building, and finance — across key sectors such as agriculture, water, and clean energy. Expanding access to clean energy has become a national priority, she noted, but “we expect to get a lot of money to ensure clean energy reaches the people as planned.”

She emphasised that grants are not charity, but an obligation rooted directly in international law. “Developed countries have the responsibility according to the Paris Agreement,” she said. “It is their responsibility because they produce this carbon in large quantities compared to us who produce little but suffer the consequences.”

Yet the UN Adaptation Gap Report 2025 paints a sobering picture: Sub-Saharan Africa alone will need US$141 billion per year by 2035, while current global international adaptation finance flows are only US$26 billion per year, leaving the region’s adaptation needs at five times the world’s current delivery budget.

With such a big shortfall, Tanzania’s hope of securing substantial grant-based funding faces serious headwinds.

Expectations are high, but the report indicates that adaptation finance is running far short of what is needed to meet adaptation goals, leaving the country’s ambitious plans haging in uncertainty.

As COP30 enters its decisive phase, the widening adaptation finance gap — now quantified in historic detail — is shaping every negotiation corridor and every political demand.

With the widening gap on adaptation finance, will Tanzania’s dream of securing more grants come true?