In 2015, Helen Sheiyo Arpake passed her Form Four examinations with marks that should have been her ticket to a professional career. Instead, they became a catalyst for a period of intense physical and emotional abuse.

“My parents did not want me to continue with school anymore,” Helen said during an interview with Nijuze on December 25, 2025. “They wanted me to be married off, to be taken to a boma”.

In Maasai communities living in Simanjiro, located in Manyara region, climate change is not just an environmental crisis but a driver of gender-based violence. When drought kills the livestock that serve as a family’s “bank account,” daughters are often viewed as the only remaining assets. In Helen’s case, the loss of cattle to drought led her family to attempt to “sell” her into marriage for survival, using violence to break her resistance when she tried to protect her right to an education.

Helen described how the abuse escalated when she refused to abandon her studies. She noted that her stepmother and other relatives influenced her father to commit acts of cruelty. “It reached a point where they took my certificates and burned them in the fire,” Helen recalled.

This destruction of her legal identity and academic future was a direct result of the family’s economic desperation following the death of their herd.

The environmental root of domestic abuse

The connection between shifting weather and domestic cruelty is a systemic issue across Tanzania. Teddy Nazery, the General Secretary at Women and Youth Tanzania (WOYOTA), explained in a phone interview on January 5, 2026, that climate change creates high-stress environments where violence thrives.

“If you look closely, you see there is a relationship,” Nazery noted. “Climate change contributes to the increase in gender-based violence”.

Nazery pointed out that as water sources dry up, women are forced to travel much further, leaving them vulnerable to assault on the road and domestic battery at home.

“A husband can tell her, ‘Why did you take so much time?’ and the husband may think she didn’t just go for water, but for something else,” Nazery added, explaining how environmental scarcity triggers suspicion and physical punishment. For young women like Helen, the “violence” is often structural—the forced end of a dream to ensure a family can eat during a dry spell.

Tanzania’s National Climate Change Response Strategy (2021-2026) acknowledges that the country lacks the capacity to address these social side effects of climate change. It identifies gender-based vulnerabilities as a critical area that requires urgent mainstreaming into all environmental policies.

Adaptation funds as a shield against violence

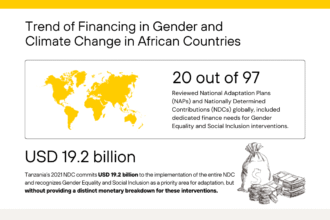

To prevent stories like Helen’s, international and national policies are calling for massive financial interventions. The 2025 Adaptation Gap Report, “Running on Empty,” warns that the world is currently attempting to build resilience without the necessary funding. This “finance gap” means that rural families remain one drought away from making the desperate, violent choices Helen’s family made.

Tanzania’s 2021 Nationally Determined Contribution (NDC) estimates a total budget of over USD 19.2 billion is required for implementation, much of which is aimed at building “climate-resilient development”. These funds, if they reach the local level, could provide the livestock insurance and water infrastructure necessary to stabilize a family’s income. Nazery stressed that interventions like “drilling wells” and “providing women with capital” are not just economic moves, but primary tools to reduce the incidence of GBV.

Regarding policy, Nazery emphasized that existing frameworks must be turned into action to protect women. She told Nijuze, “We have policies, but the implementation should reach the woman at the bottom.”

She added that policies should focus on “strengthening the systems that protect women from the impacts of climate change,” ensuring that national strategies are not just papers but tools for safety.

A stolen dream and the path to survival

Global discussions at COP 30 led to the “Belém gender action plan,” which explicitly recognizes that “gender-responsive implementation… can enable Parties to raise ambition, as well as enhance gender equality” in the face of climate change. The plan seeks to protect women in rural communities like Simanjiro by ensuring they are not the primary victims of economic loss during climate disasters.

Helen eventually managed to escape her situation and, with the help of organizations like World Vision, trained in motor vehicle mechanics—though her original dream of the skies was permanently grounded.

Today, she is a mother of three children—aged ten, six, and nearly three—and manages solar-powered water systems in her village. “I am the number one person who does many things for my children,” she said, while noting, “I don’t want to see another girl having her certificates burned like what was done to me.”

In her concluding remarks, Teddy Nazery emphasized that specific actions are required to break this cycle. “NGOs and the government must give women capital and specialized training,” Nazery stressed.

She pointed out that building infrastructure is essential to safety, noting, “If we have irrigation schemes for farmers or if we have drilled wells for mothers to get water nearby, it will help in a big way to reduce gender-based violence.” She concluded by stating that as long as environmental scarcity persists, “education must continue to be provided, as it will help women” navigate these shifting realities.