Belem, Brazil — As COP30 enters its final hours, civil society leaders have shifted from broad frustration to a focused demand: adopt the Belem Action Mechanism (BAM). While negotiators work through technical discussions, activists say BAM is the only structure in the talks that can meaningfully support communities already hit by climate impacts. In Tanzania, where traditional coping methods are no longer enough, they see BAM as essential.

The push for BAM comes from the reality that global support systems are slow and disjointed. Tanzanian women, who shoulder most climate-related labor, feel this gap most acutely. The National Climate Change Response Strategy (NCCRS) shows that as water sources dry up, women must walk longer distances to fetch water—raising both health risks and exposure to Gender-Based Violence (GBV).

A ‘one-two punch’ for health and safety

Civil society leaders believe that without a centralized mechanism like BAM to uphold the idea of a “Just Transition,” the needs of these women will continue to be overlooked. BAM aims to ensure that the shift to a greener economy includes social protections and direct support for those facing the harshest impacts.

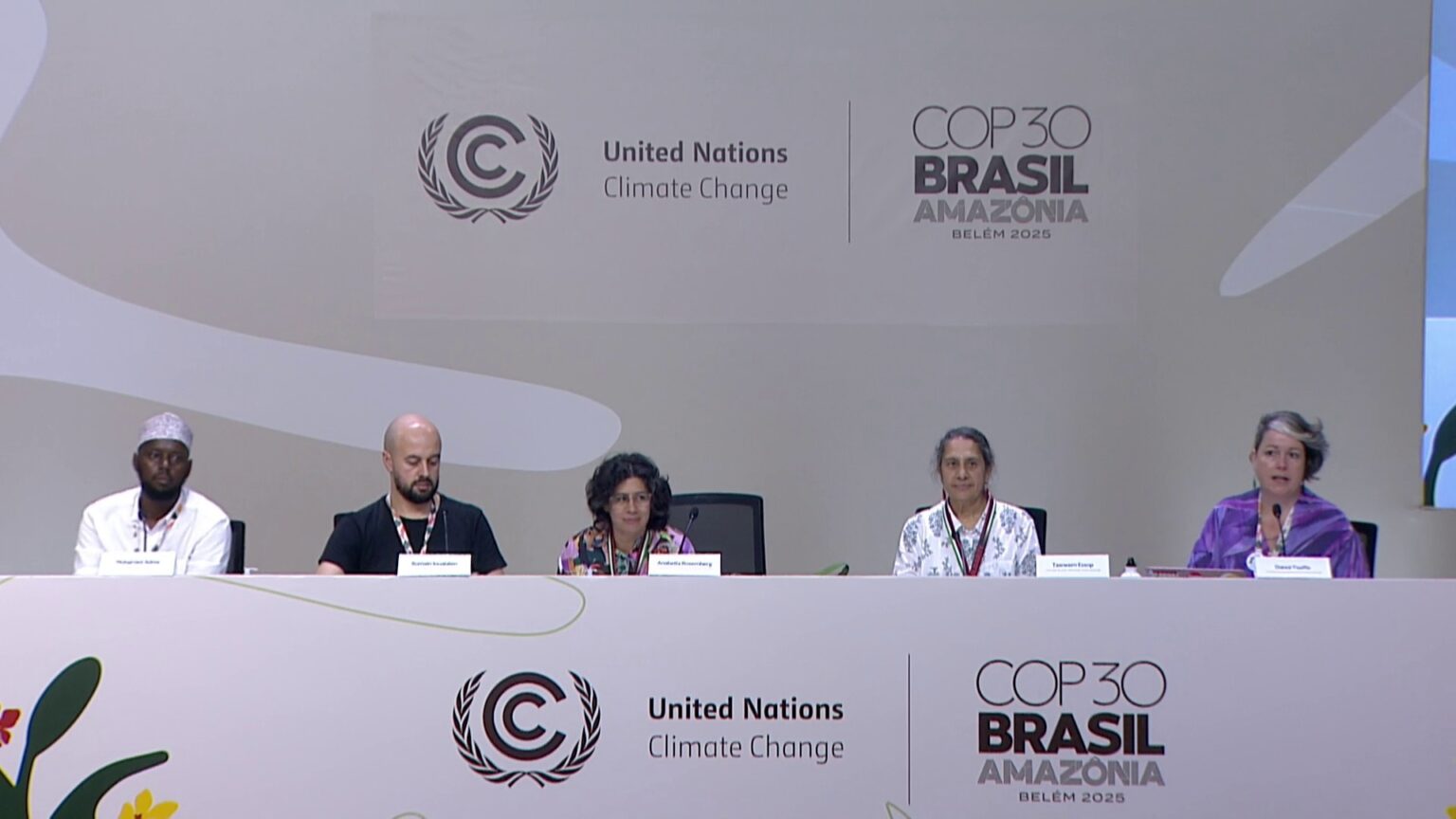

Speaking during a CAN International press conference on November 21, 2025, at COP30 in Belem, Tasneem Essop, Executive Director at Climate Action Network, said the summit must deliver more than rhetoric.

“We definitely need something more substantive. And that is where the Belem action mechanism comes in,” she told the press. “Belem can be the home for justice. Belem can be the home for a just transition.”

Without the BAM to coordinate and fund rapid adaptation responses, Tanzania’s ability to upgrade health infrastructure to cope with these shifting disease patterns is severely limited.

Ms Essop warned that without this mechanism, the summit would produce only “hot air.”

“That Belem action mechanism, of course, is a one-two punch. It addresses the fundamental need to have justice and it addresses the protection and safety and security of workers and communities,” she stressed. “Are we fighting for the hot air and where things go to die, or are we fighting for real substantial outcomes that deals with justice?”

For Tanzanian women, “justice” means funding for reliable water systems. The NCCRS notes that 92% of rural households still depend on firewood for cooking—representing millions of hours of unpaid labor. That time could be reduced through the technology transfer BAM seeks to support.

Rejecting ‘placeholders’ to save livelihoods

The urgency behind BAM also reflects the consequences of past temporary agreements. For Tanzania’s pastoralists, delays in action have cost lives and livelihoods. The NCCRS documents that the 2009/2010 drought in the Arusha region killed more than 700,000 livestock, devastating the local economy.

Without the Action and Support component of BAM—which would act as a “matchmaker” linking countries with available finance—Tanzania cannot implement the rangeland management or insurance programs needed to avoid such losses.

During the same press conference, Mohamed Adow, Founder and Director of Power Shift Africa, called for real commitments.

“What we need is concrete commitment, not placeholders, not postponing ambition to another year, to another COP, to another consultation,” he said. “What vulnerable countries require is grant-based public finance that can help them be able to build their adaptive capacity.”

A deadline for survival

BAM’s supporters say implementation must begin immediately. Climate impacts are advancing faster than negotiations. According to the NCCRS, malaria is already spreading into historically cooler highland regions such as Iringa and Kilimanjaro due to rising temperatures. Pregnant women and children under five now face increased risk in areas that previously saw low transmission.

Civil society groups argue that leaving Belem without adopting BAM would fail these vulnerable communities.

Meanwhile at the COP30 press venues, Anabella Rosemberg, Senior Advisor on Just Transition at Climate Action Network International, issued a firm challenge during November

“Civil society is asking parties to respect our collective work and agree on the BAM now,” she said. “We are asking them to guarantee a seat at the table for all of those that are rarely heard.”

For Tanzanian women, that “seat at the table” through BAM is the only way to ensure that their daily realities—drying wells, dying cattle, and shifting disease patterns—are met with real resources, not more promises.