Communities on the climate frontlines — especially women, girls, and gender-diverse people — could feel the impact of negotiations now unfolding at COP30 in Belem, where advocates say long-standing gender commitments are facing unprecedented pushback. For many, the outcome could determine whether global climate policy meaningfully reflects lived realities back home.

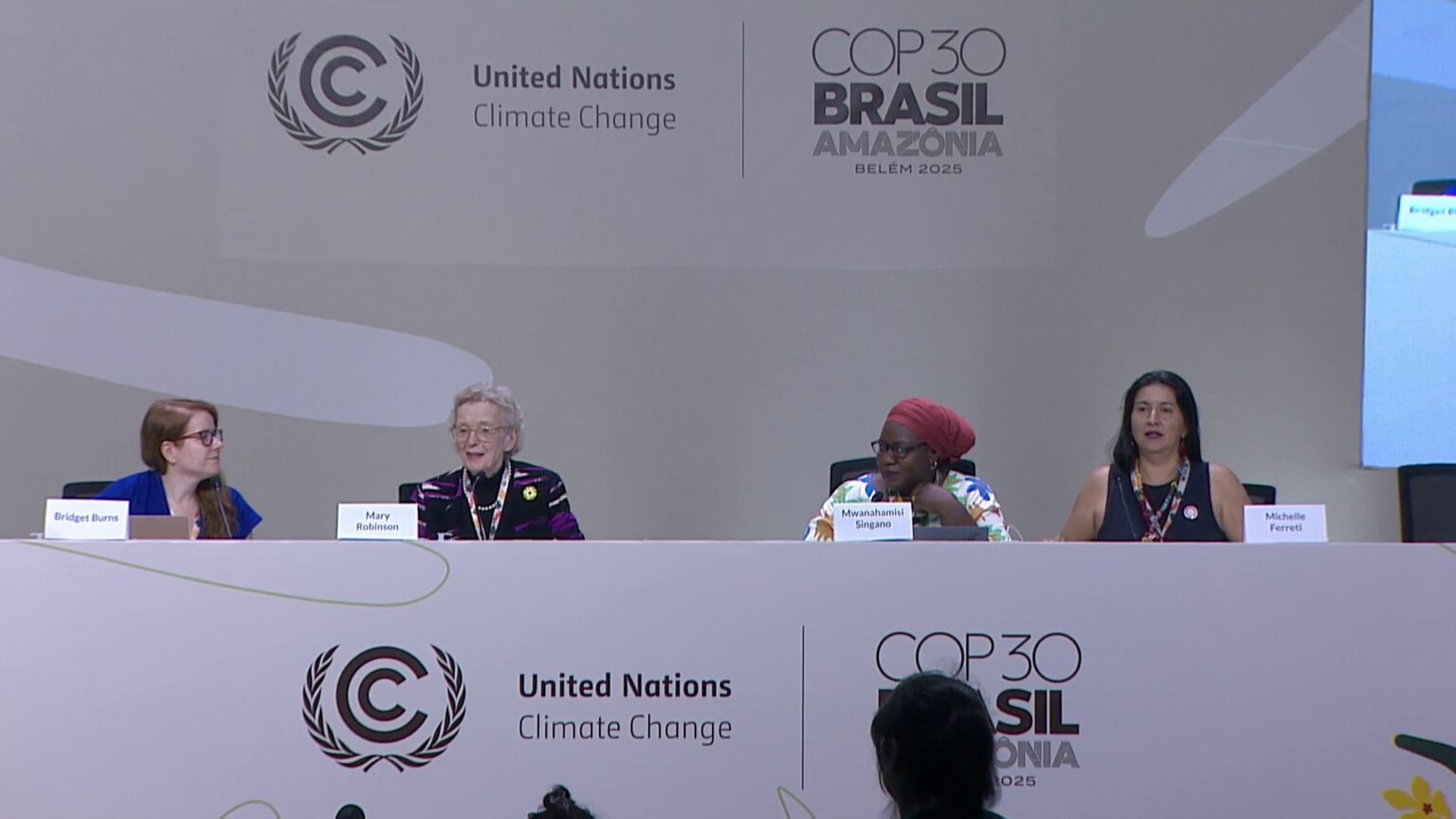

During a press conference held on November 19, 2025, at the COP30 venue in Belem, Brazil, speakers convened by the Women’s Environment and Development Organization (WEDO) said weakening the Gender Action Plan (GAP) would directly affect how climate decisions shape programmes at national and community levels.

Concerns Over Rising Pushback

Bridget Burns, Executive Director of WEDO, opened the briefing by framing what is at stake for communities that rely on gender-responsive policies to access support.

Speaking at the WEDO event titled “The GAP: Delivering a Gender Action Plan at COP30 – Current State of Play,” Burns said the discussions signal a coordinated attempt to roll back long-agreed principles.

“This is not just an alarming coordinated backtrack on language,” she explained, referring to what she called “six footnotes in the draft GAP” that attempt to redefine agreed terms. She noted that the proposed changes risk undermining multilateralism itself by allowing parties to individually interpret fundamental concepts.

Burns said such shifts, if accepted, would create barriers for communities whose climate challenges are shaped by gendered vulnerabilities. She added that past reviews have shown the need for governments — not only the UNFCCC secretariat — to lead national implementation.

“Gender equality is a precondition for effective climate action”

Former President of Ireland Mary Robinson, also speaking at the WEDO press conference in Belem on November 19, said removing or diluting gender language would weaken climate ambition.

“We call it the GAP, but actually we’ve too many gaps in Belem,” Robinson told reporters. “Gender equality is a precondition for effective climate action. Gender equality isn’t an add-on to climate policy. It’s a measure of its effectiveness.”

Robinson emphasized that women, girls and gender-diverse people are typically more exposed to climate and nature shocks, and often lead community resilience efforts. She said this makes it essential to retain clear and inclusive gender references across all negotiating items — from adaptation to finance and just transition.

She pointed out that language on gender had been bracketed with no alternative proposals. “Just take out gender. I mean, how crazy can you be?” she asked, adding that such a move is “not acceptable” in a process where parties have reaffirmed gender equality repeatedly, including through the Lima Work Programme and its renewal.

Robinson also said civil society groups such as WEDO are pushing for stronger recognition of gender diversity, reproductive health and rights, financing, and leadership mechanisms. She urged parties to uphold expert work already completed in Bonn, noting that negotiators there had “done a good job” understanding the gendered impacts of climate change.

Calls for community-level accountability

Tanzanian feminist and a global co-focal point of the Women and Gender Constituency member Mwanahamisi Singano addressed gaps between global negotiations and national implementation. Speaking during the same WEDO press conference in Belem, she said many countries previously relied heavily on the UNFCCC secretariat to lead GAP activities.

“If you look at the current version of the draft now, there is a number of activities that will be led by the government and the national government, to be specific,” Singano explained. She added that greater national ownership must be matched by public oversight. “The role me and you can play [is] to hold our government accountable.”

She also said the newly proposed nine-year GAP and the 10-year work programme create space for long-term planning and implementation, reducing the need to renegotiate the same goals each year. But she warned that efforts to remove gender language remain a real threat.

“While the danger is real on the efforts from the government, I wish to assure you as a feminist that we won’t allow that to happen,” she said. “Our livelihoods and our lives as women, as gender-diverse people should not be a privilege.”

African perspectives underscore deeper definitional challenges

Ahead of COP30, Maria Matui, Executive Director at the Tanzania-based organization WATED, told Nijuze in Dar es Salaam that differing interpretations of gender across countries have complicated negotiations.

“We, as African countries, have our own way of defining gender as gender,” Matui said. When these differences arise, she explained, documents are often set aside for later discussion — a challenge she views as one of the core barriers to progress ahead of COP30.

As negotiations continue in Belém, speakers stressed that the issue is not simply about language but about ensuring climate policies reflect the realities faced by the people most vulnerable to climate impacts. They warned that without agreed definitions and clear commitments, implementation becomes inconsistent and communities lose out on solutions designed to protect them.

For now, advocates say they are focused on holding the line. But with footnotes, bracketed text, and competing interpretations still under debate, what emerges in the final decision remains uncertain.